In packaging production, die cutting is often treated as a key step.

But on the shop floor, die cutting is not the moment your job is “done.”

When sheets leave the die cutter, they are still semi-finished.

Waste is still attached. Stacks may be loose. The output is not ready for smooth feeding into the next station.

What turns die-cut sheets into stable, usable blanks is the finishing work that happens right after die cutting.

If you understand these steps, you understand the real path from shape to shipment.

After die cutting, sheets usually go through waste removal (stripping or blanking), separation and stacking, visual checking and basic finishing, and then move on to folder gluing or other post-press operations.

In many factories, people do not label these steps clearly.

They just “do what needs to be done.”

But once you break the work down, each action has a clear purpose, and there are several common ways to handle it.

How Waste Removal (Stripping / Blanking) Works

After die cutting, the carton shape is already cut and creased.

Still, the finished blank is not fully free.

To keep sheets stable during die cutting, the layout usually leaves waste borders and connecting points.

These parts support the sheet during cutting, but they must be removed before the blanks can be handled or fed reliably.

The basic principle of waste removal is straightforward.

A stripping or blanking setup applies controlled vertical force using tooling, pins, or dedicated frames.

Finished blanks are pushed out as a group, while the waste stays in place or is collected separately.

Manual stripping does the same job, just by hand.

Mechanical stripping repeats the same movement across the full sheet with consistent pressure and timing.

So the real difference is not whether waste is removed. It is how stable and repeatable the action is.

This step has one clear goal:

release the usable blanks from the supporting waste structure.

Separation and Stacking: Turning Output Into a Controlled Pile

Once waste is removed, blanks look “finished,” but they are still not production-ready.

They may be scattered.

The orientation may vary.

Counts may be unclear.

Separation and stacking solve this.

Blanks are aligned, counted, and stacked so they can be moved and fed into the next process in a predictable way.

In smaller operations, this is often done by operators at delivery.

They receive the blanks, square the edges, and build piles on pallets.

In more continuous lines, stackers and delivery systems help maintain alignment and pile stability.

The main job is not to change the product.

It is to keep the flow steady and prevent the next station from being disturbed.

Inspection and Basic Finishing: Real, But Often Not “A Station”

Inspection after die cutting is usually not a formal, separate process.

It happens inside daily handling.

Operators check while stripping.

They notice issues while stacking.

Or they confirm quality right before feeding into the next step.

The checks are practical and visual.

Incomplete cuts.

Broken nicks.

Crease problems that look obviously wrong.

Most factories do not treat this as a dedicated machine step.

At this point, the goal is not deep measurement.

It is to catch clear problems before more value is added downstream.

Not Every Post-Die-Cutting Step Is Mandatory

There is no single “standard” finishing route that every factory must follow.

Some plants combine stripping, stacking, and quick checking into one continuous rhythm.

Others separate the work into clearly defined steps.

This does not mean one factory is always more advanced.

It simply shows that finishing is a chosen workflow.

As long as blanks can enter the next process in a stable, repeatable condition, the workflow makes sense.

Less Common Post-Die-Cutting Operations

The market also has finishing steps that exist, but are not widely used in everyday carton work.

For example, pile turning or flipping.

For example, automatic sorting when layouts are mixed.

For example, inline inspection systems focused on specific defect detection.

These options usually appear in special setups.

Very high volume. Very stable product mix. Very strict requirements for orientation or sequence.

For most normal packaging plants, these steps are not part of the default finishing flow.

Other Finishing Equipment You May See on the Market

If you explore post-press equipment, you will hear many names.

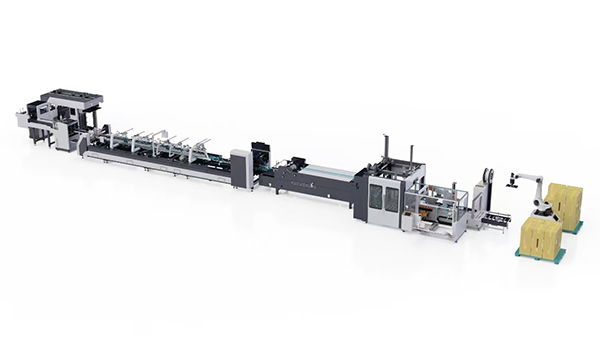

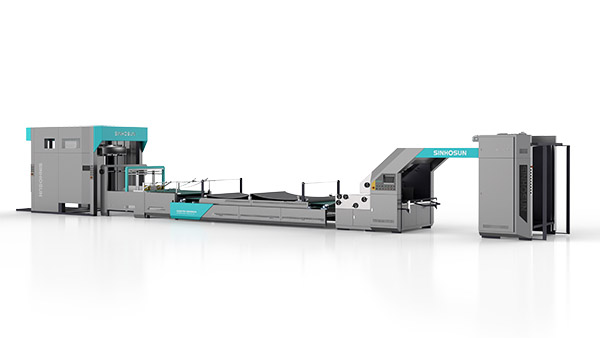

Some machines focus on waste removal, such as stripping units or blanking machines.

Some focus on stacking and pile handling, such as stackers, delivery systems, or pile turners.

Others support inspection and organization, sometimes as add-ons rather than standalone machines.

These machines exist to solve specific problems.

They do not define a universal process.

Knowing what they are helps you understand the industry landscape.

But it does not automatically mean you need them in your own line.

Conclusion

What happens after die cutting is not one action.

It is a set of finishing moves that prepare blanks for the next stage.

Remove what is not needed.

Organize what is usable.

Make the output stable enough to feed into folder gluing or packing.

Once you understand the purpose and the principle behind each step, post-die-cut finishing stops feeling like a “mystery area.”

It becomes a workflow you can describe, compare, and improve—at your own pace, and in your own way.