In many packaging plants, waste removal only becomes a problem after die-cutting speed increases. Sheets come out faster, but waste does not leave cleanly. Operators stop the machine, pick scraps by hand, and restart again. If this stage depends on manual fixing, higher die-cutting speed does not improve output. It creates labor pressure, unstable quality, and delivery risk instead.

The real issue is not speed. It is mismatch.

Slow waste removal after die cutting is rarely caused by operator efficiency. It is a system bottleneck created when die-cut structure, waste layout, and removal method do not match. A sustainable solution is to plan a clear and repeatable waste exit path during die design, and replace high-frequency manual stripping with stable automated stripping or blanking processes to improve total line efficiency and stability.

When we review production lines, we often find machines running well on their own, but the workflow is not aligned. Waste removal is the first place where this misalignment shows. The right question is not “How can we clean faster?” but “Is our current waste removal method suitable for our product structure and output target?”

Why Faster Die Cutting Often Makes Waste Removal the Bottleneck

When die-cutting speed increases, waste volume per hour increases as well. Manual stripping has a fixed speed limit. It does not scale.

At higher speeds, waste pieces overlap, bend, or lock together. Operators must stop the machine more often. Small delays add up. Output becomes unstable even though the die cutter itself is faster.

This is why many factories feel they upgraded capacity, but shipment lead time did not improve.

Die-Cut Structures That Decide Waste Removal Difficulty Early

Some products are difficult to clean by nature.

These include:

- Small internal waste pieces

- Dense waste distribution

- Narrow bridges between blanks

- Thick board or laminated materials

In these cases, waste does not fall naturally. If the structure was not designed with a removal path, no operator skill can fix it consistently.

Waste difficulty is often decided at the die design stage, not on the shop floor.

Structure Problem or Equipment Configuration Problem?

You can use one simple rule.

If waste removal speed changes with operator skill or shift, it is a manual limitation.

If waste removal is slow on every shift, with every operator, it is a structural or configuration issue.

If waste stays connected or partially attached, it is a structure problem.

If waste separates but cannot exit smoothly, it is a removal method problem.

This distinction matters. Adding labor only hides the problem. It does not solve it.

What Equipment Can Provide Stripping and Blanking Functions?

There is no single solution for all waste removal problems. Different waste structures require different stripping methods.

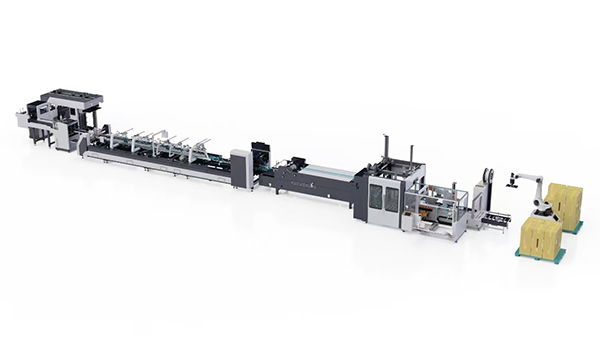

A stripping blanking machine removes internal and external waste through mechanical motion. It works best when waste layout is dense and repeatability is required. Compared with manual stripping, it delivers stable output and reduces stop-start interruptions.

A pneumatic waste stripper uses air pressure to push waste out of the sheet. It is effective for medium-complex layouts and lighter board, especially when flexibility is needed without full automation. However, its performance still depends on waste size and consistency.

For products with small holes or enclosed waste, a drilling-based waste removal unit is often used. By creating dedicated exit points, it solves problems that stripping alone cannot handle. This method is structural, not labor-driven.

When production volume increases and labor stability becomes a concern, blanking machines offer the highest level of consistency. They separate finished blanks from waste stacks in one controlled process, making downstream folder gluer feeding far more stable.

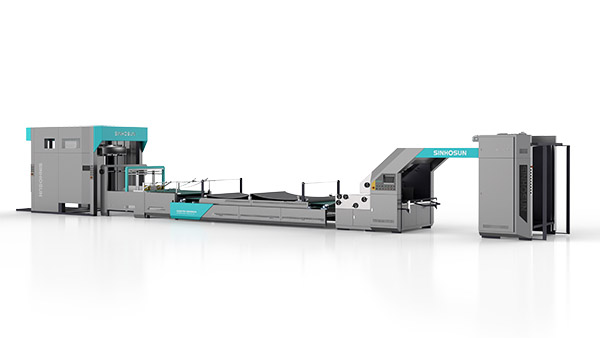

At SINHOSUN, many factories start with stripping to regain control, then move to a dedicated blanking machine when output targets and labor reduction become long-term goals. Our blanking machines are designed around real die-cut structures, not ideal samples—because stable waste separation is what protects delivery schedules in daily production.

Conclusion

If waste removal after die cutting is slow, the line is giving you a signal. The current method no longer fits your product structure or output goal. The right decision is not to push people harder, but to realign structure, process, and equipment.

That is how you protect delivery, quality, and long-term efficiency—from the factory’s side, not the brochure side.